THE

ANNEX

NEWS

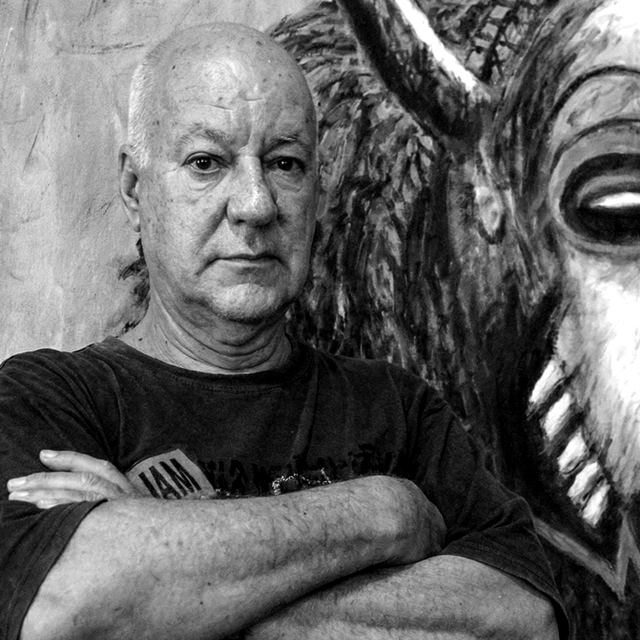

Photographs by Pedro Abascal

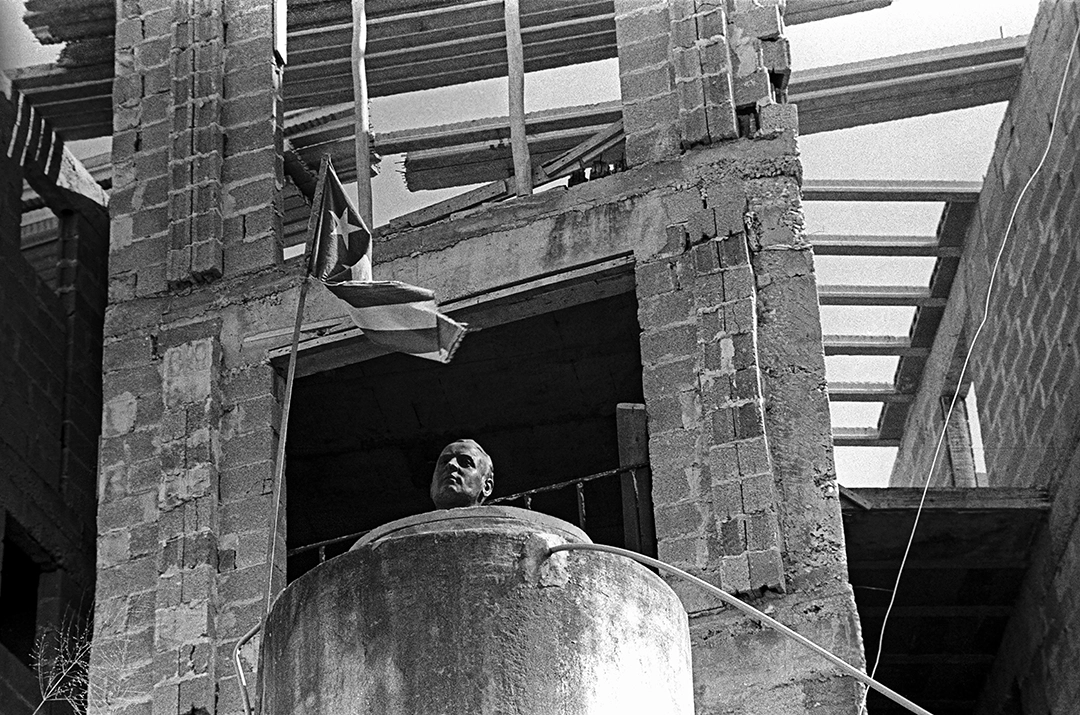

There are cities that return the gaze: they do not yield docilely to the frame, but instead address the viewer directly. They demand a way of looking that does not reduce, that does not close off meaning. Havana, in this Dossier conceived by the Cuban photographer Pedro Abascal, appears as an entity that observes, folds, and tenses itself; it refuses to become a mere setting or backdrop.

Abascal does not document: he interrogates. He does not seek the tourist postcard nor the ruin, but rather the fold where the everyday becomes a sign. His camera does not capture—it converses, and within that conversation the visible—a gesture, a body, a texture, a transparency—becomes unstable or settles into a state of waiting. Nor does it impose itself; instead, it coexists with each scene in which it crosses paths with people who move through, wait, improvise—bodies that inhabit the city through vulnerability and dignity.

Even when the photographer’s own figure appears in some of these images, it does so discreetly, inscribed in glass, mirrors, and translucent surfaces of the environment. This presence does not interfere with the rhythms of everyday life; it integrates naturally, as if the city itself absorbed it without disturbance. It is a presence that assumes its place without claiming protagonism.

There is something of both archive and poem in this Dossier, which began to take shape in the early years of the final decade of the twentieth century on the Island—an era marked by penumbra and hardship, extending into the present through chronic fluctuation. Each photograph seems like a marginal note to a history that resists being fully written, that refuses closure. There is no impulse toward denunciation or ornamentation; rather, one perceives a search for a humanity that endures in fragility, sustained equally by light and shadow. These images do not illustrate a thesis nor respond to a slogan. They are, instead, moments of open conversation with the city, with its inhabitants, with its suspended rhythms…

There is no intention here to monumentalize or aestheticize precarity; what emerges instead is an ethic of attention, a slow mode of approach that stands in opposition to the rapid consumption of the visual.

Recognized as an active member of the generation of photographers who reformulated the paradigm of Cuban photography inherited from previous decades during the 1990s, Abascal did not dismiss the best of that tradition. He conjugated it with the legacy of significant international references, which he studied in depth and assumed critically and selectively, remaining aloof from the influence of fashion. This has enabled him to imprint his work with a personal signature in which testimony and poetry merge into an effective alloy, giving rise to images that invite prolonged engagement—something also evident in Havana Dossier.

On numerous occasions, Abascal has expressed his discomfort with the impulse to confine photography within rigid categories, particularly with attempts to label his work as “documentary” (understood in its most traditional sense: capturing reality as it is). Aware that every photograph is a choice—of framing, moment, distance, light—he understands that classifying his work as document alone would risk diminishing its poetic reach, ignoring its aesthetic, emotional, and philosophical dimensions.

Abascal does not aspire to capture an “objective truth,” but rather an intimate truth—one that emerges from a form of knowledge grounded in personal experience and sensitivity, not in data. In Havana Dossier, the documentary and the poetic coexist and overlap. The images are not merely informative; each contains fragments of the everyday life of a city that, when read as an essay, form a paradoxical core in which resistance and resilience, resignation and hope, remnants of utopia and dystopian traits merge in asymmetrical tension.

Beyond his technical and conceptual mastery of photographic language, what is particularly admirable is the singular manner in which Abascal directs his gaze toward the apparently ordinary to deliver images of elevated aesthetic quality, bearing multiple layers of meaning that touch upon fundamental aspects of human existence. Perhaps herein lies one of his most significant contributions to Cuban photography: the ability to render the essential visible without resorting to spectacle.

Without excluding other possibilities, these images may be read as one reads a field notebook: attentively, with doubt, with the awareness that every “mark” is also an omission. For in Havana Dossier, what is not shown is as eloquent as what is seen. And in that tension between the visible and the elusive, between what is denoted and what remains hidden, a space opens for imagination and experience.

Ibis Hernández Abascal

Art critic and independent curator

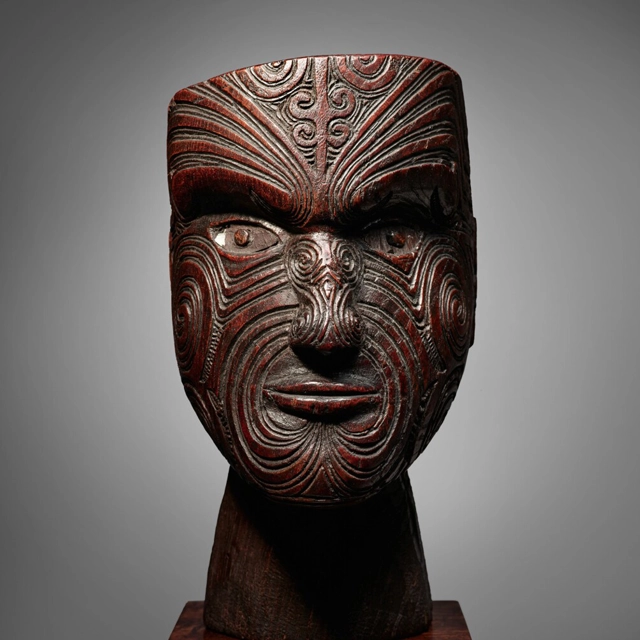

It is generally understood that national museums ought to be the natural custodians of their cultural memory. Spaces where the history of national art is presented in an ordered and intelligible form. Where foundational images can still be contemplated. Yet, primarily for reasons of funding, an increasing number of state institutions...