THE

ANNEX

NEWS

A beautiful vista of Havana Bay, framed by the large window beside the entrance, catches the first-time visitor at once. Nothing more is needed for the restless collector of unrepeatable instants: views that do not tolerate staging—views that do nothing but awaken the desire to contemplate them, to capture them, to possess them. A coffee becomes an invitation for the newcomer. We already have something in common.

Pedro Abascal is, in essence, one of the most outstanding makers of photography in Cuba over the last decades. Heir to great masters he considers himself fortunate to have known—Alberto Díaz (Korda), Raúl Corrales, and Ramón Martínez Grandal—he acknowledges in the latter the kind of influence only a mentor can exert. And yet Abascal bears a signature that sets him apart from his contemporaries. He is not drawn to the grand format. His language is intimate, private—like “a small poem to be read in a low voice to a select audience,” as his tutor and friend Grandal used to say. He recognizes the value of his work when an image triggers reflection, when it allows a message to be teased out, or when it simply opens a passage back into time through the memory of something once lived. He feels his work has fulfilled its task the moment it does something to someone—when it becomes, in a sense, a mirror for whoever looks at it.

Neither the city’s wrinkles nor its paradisiacal spaces are his focus. Rather, his intuition moves toward the rough edges—the stumbling blocks—of society, not by predetermination, but by the action of chance: seizing moments that can only be captured without warning or arrangement, only when reality is perceived through the lens of a camera carried everywhere, always at the ready.

His photographs contain a great deal of humanity; and yet his work is more about photography itself than about the subject. Composition is the central axis of his practice, shaped by singular elements such as framing, the chosen angle, and contrast. Abascal works light and shadow through black and white, but also through color. He thus separates his work into two folders (two photographic essays): Dossier Habana on the one hand, and Habana Color on the other. They are not opposites; each possesses its own expressive riches and, above all, conceptual ones. In the second case, color is privileged—seeking the prevalence of brightness and light in order to draw the gaze closer to reality, to ourselves, to the human being. He converses, argues, and uncovers not what we already know and see, but what underlies it: the ideas that shift behind the “official” image. It is never only one… there is an optical game that can pass unnoticed at first glance, but if the eye lingers, there the true meaning appears—precisely in what a quick panoramic look almost never manages to identify.

In this sense, a self-referential bias brushes against these images—sometimes forcefully, sometimes lightly; it is enough to move closer to the photograph for details to reveal themselves. Childhood left a decisive mark on his work. The hours spent waiting at the barbershop of the Casino Deportivo Habanero, seated with mirrors in front and behind, stirred in him an unease before that reflected image—once, and again, and again: a form of introspection, the image of the image. That is why his work finds parallels with meta-narrative and reiterated discourse. In his mind he played at imagining thousands of stories, of realities, all born from those repeated images… mirrors, reflections, to reflect—to think, to imagine.

He needs his work to be like a book: something that can be read and observed, something one can return to whenever one wishes—something capable of offering new readings, thoughts, and sensations each time. And yet, with extraordinary humility, he remarks that his images “are a catalogue of errors.”

We have previously discussed how a photograph — or an image — can rearticulate the public perception of reality. How it can encapsulate experience, much like a verb does, rendering it transferable, exposable, and legible in a specific way. Any story is a continuum, difficult to apprehend in its full extension and multidimensionality. In order to be understood and fixed as experience — and as argument — it must be reformulated through its most expressive qualities...

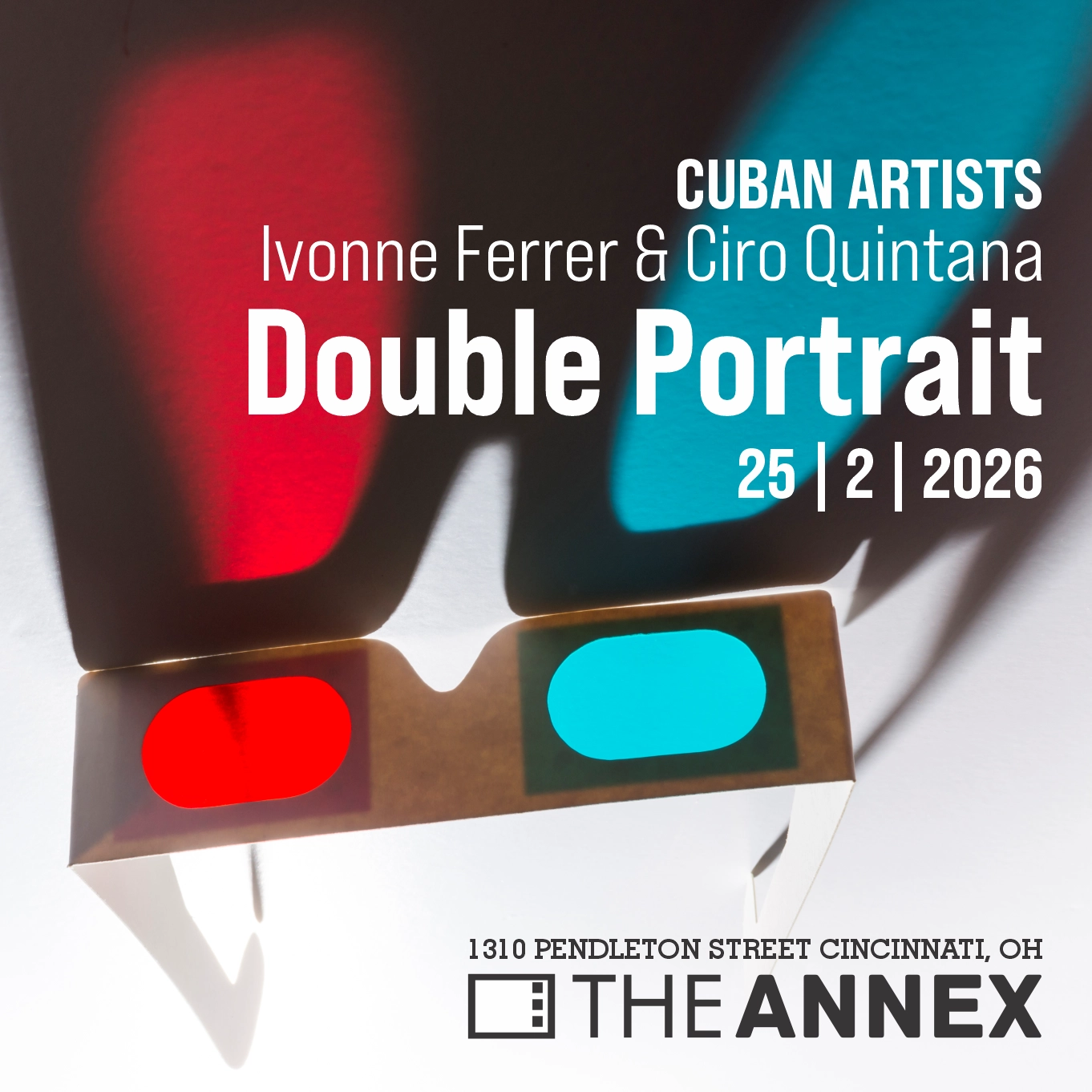

Cuba and Spirit in the Work of Ivonne Ferrer and Ciro Quintana