THE

ANNEX

NEWS

Anyone who approaches Pedro Abascal’s photography and speaks with the author about the spontaneous nature of his scenes cannot help but think: he’s taking me for a fool. So accustomed have we become to an art of effects—an art frequently structured around spectacle, one that opportunistically deploys “the technological” to shield the fragility of its premises—that it feels like a deception when he claims he neither goes out hunting for images nor resorts to manipulation of any kind to produce photographs of such suggestive force. And yet his images, like jazz pieces—as the author himself compares them—charge the viewer with a singular energy, constantly rereading their environment through an optic that foregrounds the polarity of meanings.

Twenty small-format works comprise Urban Landscape, his most recent exhibition at the Korda Gallery, House of the UPEC in Pinar del Río, inaugurated within the framework of the Provincial Visual Arts Salon “October 20.” These are proposals that must be seen again and again to yield their full measure of commentary, despite their susceptibility to being labeled documentary. They form part of a broader essay Abascal has been developing for some time, titled Dossier Habana. From the outset, his practice has sustained the same existential concerns, reaching a climactic point during the 1990s with the emergence of young photographers determined to unsettle the notion of reality upon which photography had until then operated. Experimentation with unconventional techniques and supports, manipulation of the lens, and the questioning of the epic character that defined much of Cuban photography—among other conceptual and formal premises—gave rise to a renewal of the genre that enabled the appearance of significant works in the history of Cuban visual culture.

These recent pieces operate through a language dense with metaphors and allegories that regard, with sharpened suspicion, the contrasts embedded within contemporary Cuban society: the merolico and the tourist, high-tech architecture and ruin, insider and outsider, permanence and departure, the visible and the unfathomable, the mundane and the divine. Abascal employs mirrors, rear-view mirrors, and shop windows to establish multiple planes of perception, which in turn function as superimposed planes of meaning. These elements enrich his metaphoric structure, articulating reflections on confinement, precarity, and isolation; yet beneath them, despite every contradiction, there persists the suggestion that Havana—to invoke the part in place of the whole—still retains its charm.

Resolved with apparent simplicity through the gelatin silver process, these works nonetheless constitute a piercing essay on the urban landscape, where the human presence carries decisive weight—even when absent from the visible scene. The mannequin emerges as another recurring element within this discourse, perhaps owing to its ludic and reverential nature, fundamentally opposed to what one expects from a citizen endowed with agency over their immediate reality.

Many eloquent works from the Urban Landscape series could be invoked: the image divided into two registers, where a graffiti-laden wall occupies the foreground while, in the background, a passerby descends a staircase—the common man enclosed within a concrete structure resembling the very hat resting upon his head. Or those instances in which, deliberately, the artist commits “technical errors” in order to insert himself into the frame, as when the shadow of his head appears crowned by a henequen plant. It bears noting that this shrub, among its many uses, has been planted near coastal zones as a defensive measure against aerial invasion, its rigid form capable of obstructing parachute landings. One possible reading points to the omnipresence of the defensive character of the Revolution.

Most photographers today construct their images through montage, found objects, or various forms of physico-chemical manipulation; yet the author feels no passion for the trick. He prefers instead to capture “the decisive moment,” as the Frenchman Cartier-Bresson once did, who understood the creative act to culminate in the discovery of an optimal angle of vision at the precise instant of its appearance. The Cuban’s works are the result of an eye trained to detect coincidences that crystallize into texts. The interplay of light and shadow likewise serves him as a means of speaking about a plural, elusive, dynamic context—one that resists exhaustion within a single reading, and that, in its plastic articulation, interrogates the viewer regarding the nature of what is understood as “real,” and the artistic possibilities inherent to photography itself.

Each photograph in Urban Landscape constitutes an essay on Cuban reality in its differences, ambiguities, and ambivalences. On one side stands the world of corporations, the extraction of hard currency, joint ventures, and urban redevelopment; on the other, the condition of the ordinary Cuban citizen: burdened, constrained by housing shortages, transportation failures, and the precariousness of daily subsistence, yet equally attentive to the transformations unfolding within the urban environment. The critical force of these works resolves itself with subtlety, yet with the sensitivity that defines Abascal’s most enduring contributions. Despite occupying a place within the history of Cuban visual culture, he has not been among its most promoted figures—perhaps because he remains so deeply embedded within the landscape that he suffers its wounds.

Note

Merolico is a culturally specific term in Cuban and broader Latin American contexts referring to an itinerant street vendor who sells a heterogeneous assortment of objects—often inexpensive, improvised, scarce, or of uncertain origin and quality. Unlike a conventional merchant, the merolico operates at the margins of formal commerce, relying on improvisation, persuasion, and opportunistic display. The figure carries a strong symbolic charge: he embodies both economic precarity and ingenuity, functioning as a living index of informal economies, survival strategies, and the porous boundary between necessity and invention.

Within visual and literary discourse, the merolico frequently appears as a metaphor for adaptation, ambiguity, and the unstable value of objects and meanings in societies marked by scarcity and transition.

We have previously discussed how a photograph — or an image — can rearticulate the public perception of reality. How it can encapsulate experience, much like a verb does, rendering it transferable, exposable, and legible in a specific way. Any story is a continuum, difficult to apprehend in its full extension and multidimensionality. In order to be understood and fixed as experience — and as argument — it must be reformulated through its most expressive qualities...

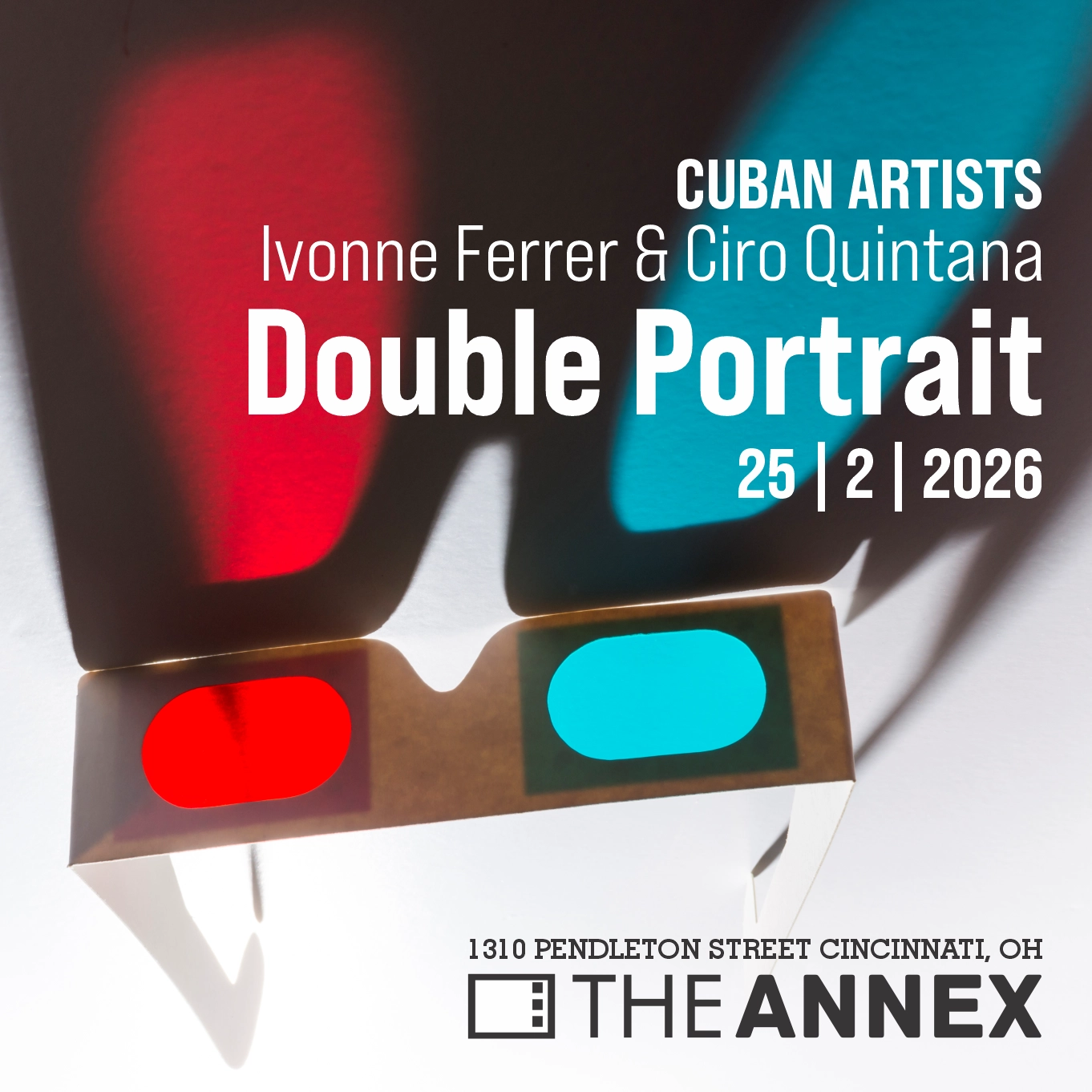

Cuba and Spirit in the Work of Ivonne Ferrer and Ciro Quintana